with unc kasama

Finding community

An interactive photostory following members of UNC Chapel Hill Kasama through traditions, history, and community.

UNC Kasama 2023-2024 executive board retreat (Khristine Bautista)

Student cultural organizations are typically viewed as spaces where students “preserve cultural traditions” and “reconnect with their roots.” While this is true in many ways, clubs at the collegiate level offer more complex takeaways (Ngo, 2015). In educational institutions, clubs are a special place where students can reconcile the power dynamics of reconnecting with culture whilst existing in a reality of coerced assimilation; serve as an act of resistance that redefines identity exploration; allow Southeast Asian students to have a voice and reconcile their identities outside of the pan-Asian context when they are drowned out in pan-Asian organizations (Ngo, 2015; Hernandez, 2017; Ocampo 2013).

Most importantly, cultural organizations give students the opportunity for cultural validation, which plays an important role in the success and retention of Southeast Asian college students (Maramba, 2014). Cultural familiarity, expression, advocacy, and knowledge contribute to developing a sense of cultural validation, which are aspects that UNC Kasama has provided for its members, creating a welcoming, family-like environment that lasts beyond graduation.

Horacio Araneta is the cultural chair at UNC Kasama, the Filipino-American student organization at UNC Chapel Hill. Araneta joined because of an upperclassman friend who brought him to a Kasama meeting during his first year. After meeting a community that helped him “come out of his shell,” he’s found joy in being a part of the club ever since.

UNC Kasama’s impact goes beyond the general body meetings that Araneta leads. He plays in a Filipino basketball league in Durham with some of his friends from Kasama, their tinikling dance team performs at the UNC “Journey into Asia” showcase, and the club has family trees that extend back multiple generations. The club is also a space for the broader Southeast Asian community at UNC: Araneta mentioned that members from the Vietnamese Student Association often join events as well.

"I like meeting more Filipino people and not even just Filipino people – just meeting people who are interested in the culture."

Horacio poses for a portrait outside of Hanes Art Center at UNC Chapel Hill

A yearly tradition, “Halo Halloween” is an event where members get together to dress up in halloween costumes and eat halo-halo. As seen here, members of the executive board poured condensed milk into blended ice to prepare servings for members.

Halo Halloween

Toppings included ice cream, nata de coco (coconut gel), macapuno strings (coconut strings), and red beans.

After Araneta taught the “Halo Halloween” attendees about Filipino folklore, the history of halo-halo, and how to say “I’m scared” in Tagalog, members lined up to receive a serving of their own.

Aside from enjoying halo-halo together, members showed off their Halloween costumes down the makeshift runway. Groups of friends lined up to strut as board members queued songs on Spotify; others gathered at the photobooth as the crowd cheered on. Attendees floated around the room, stopping to say hi to one another or take a swing at the sword prop that someone brought to the event.

Students participating in the event were able to experience cultural knowledge, familiarity, and expression through enjoying a halo-halo together – new for some but familiar for others (Maramba & Palmer, 2014). For Araneta, it was an opportunity to teach the Tagalog that he’d recently started learning as a way to better communicate with his family.

Leading up to the D7 competition, UNC Kasama members attended weekly practices in different spaces around campus.

D7 Olympics

Filipino Intercollegiate Networking Dialogue (FIND) is an organization that brings together Filipino and Filipino-American students from Maine to Florida. Schools part of this organization are divided into nine different districts based on state proximity. UNC Chapel Hill is part of D7, which includes Central & Southern Virginia along with North Carolina.

In the D7 Olympics, the nine schools part of this district come together to compete against each other in various games. Two first-years at the practice commented that they both decided to join because they wanted to meet more Filipino students and be with their friends.

However, they also both pointed out that games played at D7 were culturally significant. Christian said that hearing his parents relate the games – such as Patintero (block the runner) – back to their childhood made him more interested in Filipino culture. Beatrice spoke about how participating in D7 helps her feel more included in her family’s parties.

Christian (far left) talks with an older Kasama member while they wait for the game to begin.

"D7 is mostly Filipino party games and it [makes] me feel a lot more included in my family’s parties if I knew how to do it and master it."

Beatrice (left) prepares to play Batuhang Bola

UNC Kasama at the 2023 D7 Olympics (Khristine Bautista)

In a multiple case study on the identities of immigrant college students in a Filipino Language Club, a critical point of cultural familiarity and expression that the organization provided was allowing students to “bond while reminiscing about childhood familiarities, such as Tagalog jokes they heard from family” (Benetiz, 2019). Christian and Beatrice’s recognition of how D7 games connect with those they’ve seen their families play reflects this similar bond.

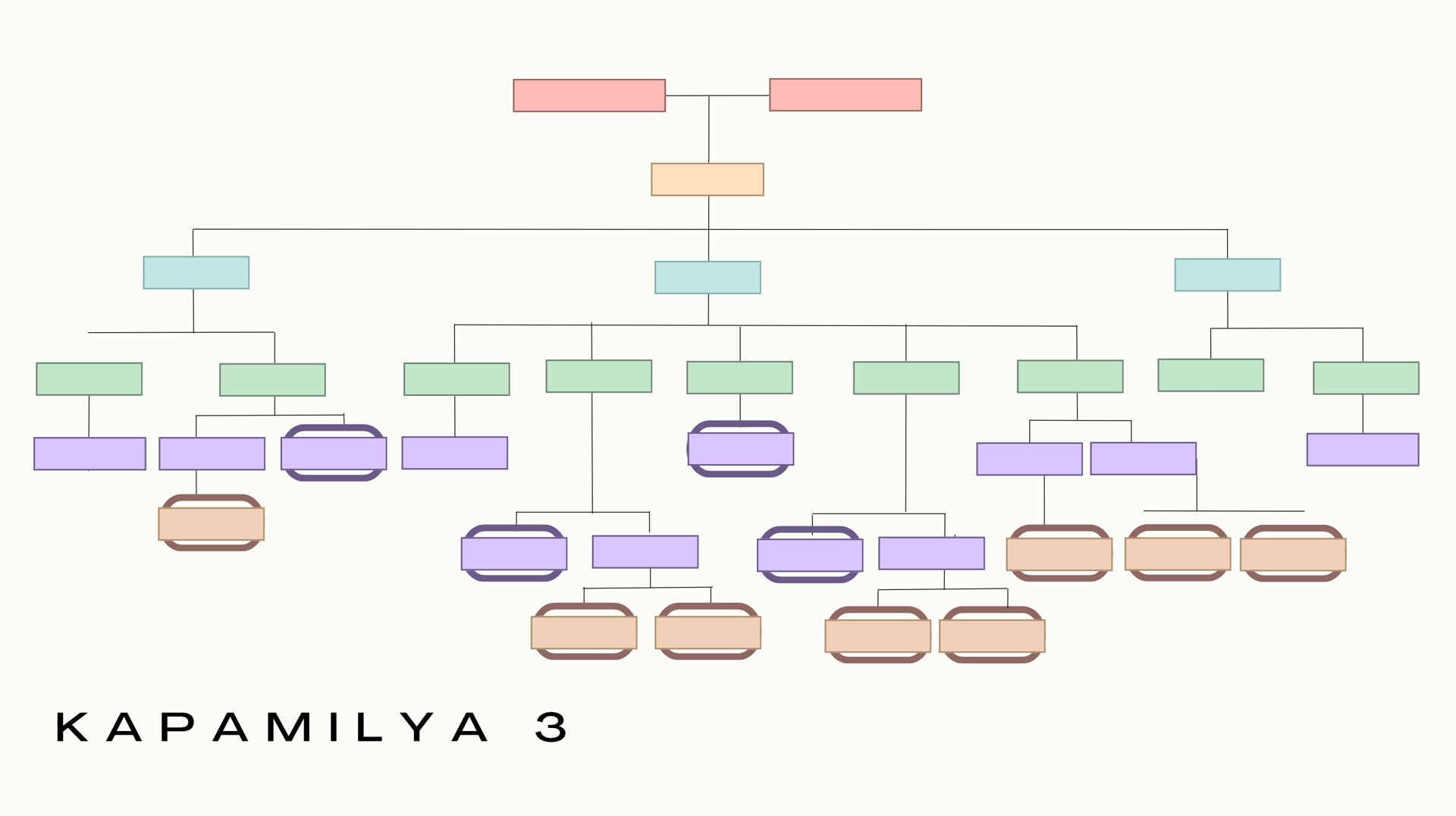

Traditions of creating "families" for Kasama members began in 2017.

Photo credits to Khristine Bautista

kapamilya Reveals

Starting in 2017, UNC Kasama began the Kuya/Ate (brother/sister) pairings and Kapamilya (family) tradition that aimed to create stronger bonds between new and old members. Older family members, and even the ones who “started” the family stay involved with their lineage.

Like Araneta, Khristine Bautista, Kasama’s historian, heard about and decided to join Kasama through a family friend. She has met her big’s big, and speaks of the sense of community she felt when she first had dinner with her Kasama family. Through sharing a meal, Bautista found out that she and her big’s parents lived in the same part of the Philippines, and that they had North Carolina hometowns located only 30 minutes away from each other.

Kapamilya 2 poses for a family portrait in 2023 (Khristine Bautista)

Khristine and her little (Khristine Bautista)

"That moment solidified my desire to join Kasama, [I was] drawn to its close-knit community and the opportunity to connect with individuals who shared my experiences."

Khristine's Kapamilya tree (Khristine Bautista)

Jezie Salvador, Kasama's publicity chair, created the 2023-2024 family trees that keep track of lineages. Now, there are a total of six Kapamilyas, continuing to branch out during the sixth year of the tradition.

Bautista notes that she went to a high school with “minimal Filipino representation,” apart from her mother who was a teacher at her school. As a result, she lacked a support system in that environment. The sense of belonging she found in college through the UNC Filipino community and her Kapamilya has been able to fill that gap for her.

Cultural familiarity, opportunities to stay connected with those with similar cultural backgrounds, is yet another aspect being a part of a Kapamilya provides (Maramba & Palmer, 2014). The new support system Bautista describes as a result of cultural familiarity reflects another student’s experiences at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa of how her school’s Filipino organization “reinforced her previous conceptions of her Filipino and Ilocano identities and established support for these identities” (Benetiz, 2019).

UNC Kasama's tinikling dance team practices in the fall semester and performs at various galas in the spring semester.

TInikling dance team

To start rehearsal, the dancers began with the parallel pairs of bamboo poles lying flat on the ground.

After they reviewed the choreography, the “clappers,” dancers who move the poles, joined in.

UNC Kasama’s tinikling team usually performs at the Journey Into Asia (JIA) showcase hosted by the UNC Asian American Student Association (AASA) in February. They also perform at Kasama’s own gala and others they’re invited to, such as the NC State Filipino-American Student Association’s Gala.

The dance team’s sense of community creates a chance for students to experience cultural expression and knowledge through learning traditional dance and being able to perform it at various galas (Maramba & Palmer, 2014). Throughout the rehearsal, the teammates clapped and cheered on one another but also playfully teased each other. The group was serious about mastering the steps, but left time to goof around; a heated debate about the merits of Insomnia and Crumbl cookies broke out in the middle of the practice.

Practicing the transition between two sections of the choreography

A part of the dance where the "clappers" lift the poles and dancers duck under.

Alumni remember UNC Kasama as a critical part of their college experience.

Photo credits to Caroline Wilkins

staying connected to community

Caroline Wilkins, who graduated from UNC Chapel Hill in 2014, says that some of her closest friends are the people she met during her time at UNC Kasama because of the bond they created by “having a Filipino background or being first-generation Filipinos/Asians.” Wilkins recalls that a lot of the members of Kasama weren’t Filipino and had varying backgrounds, which she credits to the “warm and welcoming nature of the executive team and members.” The club was simply a space where people could share culture and learn from one another.

The welcoming aspect of the club is not unique to UNC Kasama: Bayanihan, the Filipino student organization at Central University, attributes its “extremely open and social nature as a large factor in recruiting non-Filipino members from the ranks of other student organizations” in contrast with other pan-Asian organizations that can seem exclusive to students (Hernandez, 2017).

Help for Haiyan Charity Event (Caroline Wilkins)

When Wilkins was growing up, she didn’t have many Filipino friends due to the smaller Filipino community in Winston-Salem at the time. Kasama not only allowed her to reconnect with her culture through learning and teaching Filipino dances for the first time and leading Tagalog lessons, but also allowed her to grow confidence through taking on tasks as part of the executive board.

"It felt like family away from home and made my experience at Carolina even better."

UNC Kasama beach trip (Caroline Wilkins)

Wilkins was able to learn how to partner with other organizations, recruit members, run ticketing for basketball games, and fundraise. Her description of her experience with Kasama highlights multiple aspects of cultural validation, particularly cultural advocacy as she was able to advocate for the club on behalf of the executive board (Maramba & Palmer, 2014).

UNC Chapel Hill’s Kasama is not only a welcoming space of community for Filipino students but also the broader Asian community. The various aspects of cultural validation that the organization has created for its students has been critical for members’ validation of identity, formation of support systems, development of close friendships, and opportunities to connect with their family.

history, traditions,

community.

UNC Kasama at the 2023 D7 Olympics (Khristine Bautista)

Benitez, S. S. (2019). A multiple case study on the identities of immigrant college students in a filipino language club (Order No. 13883478). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (2299447787). Retrieved from http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/multiple-case-study-on-identities-immigrant/docview/2299447787/se-2

Hernandez, X. J. (2017, March 16). Filipino American college student identities: exploring racial formation on campus. Retrieved December 3, 2023, from Illinois.edu website: https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/items/102330

Maramba, D.C., & Palmer, R.T. (2014). The Impact of Cultural Validation on the College Experiences of Southeast Asian American Students. Journal of College Student Development 55(6), 515-530. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2014.0054.

Ngo, Bic (2015) "Hmong Culture Club as a Place of Belonging: The Cultivation of Hmong Students’ Cultural and Political Identities," Journal of Southeast Asian American Education and Advancement: Vol. 10 : Iss. 2 , Article 2. DOI: 10.7771/2153-8999.1130

Ocampo, A.C. (2013). “Am I Really Asian?”: Educational Experiences and Panethnic Identification among Second–Generation Filipino Americans. Journal of Asian American Studies 16(3), 295-324. https://doi.org/10.1353/jaas.2013.0032.

Park, J.J. (2014). Clubs and the Campus Racial Climate: Student Organizations and Interracial Friendship in College. Journal of College Student Development 55(7), 641-660. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2014.0076.

Simpson, J., Bista, K. (2023) Examining Minority Students’ Involvements and Experiences in Cultural Clubs and Organizations at Community Colleges, Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 47:2, 79-89, DOI: 10.1080/10668926.2021.1934753

Works cited

UNC Kasama

Mireya de los Reyes, Khristine Bautista, & Horacio Araneta

special thanks

learn more

@unckasama